Tagged: 5/5

The Song of Roland

The Song of Roland, translated by Frederick Goldin, 5/5

The Song of Roland, translated by Frederick Goldin, 5/5

I can’t say I enjoyed reading this second translation of the epic poem as much as the first, but that is probably not a reflection of each version’s merit so much as the fact that reading The Song of Roland twice in two weeks is too much. Goldin’s translation is longer and seems much more true to the original from a grammatical point of view, but I found it to be less accessible than Luquiens’ version, which is more emotional and dramatic, while being less wordy. There is a sort of Old Testament rhythm and repetitive style to Goldin’s work that made it difficult not to zone out while reading.

Here is the opening laisse from each version for comparison:

Charles the King, our Emperor, the Great,

has been in Spain for seven full years,

has conquered the high land down to the sea.

There is no castle that stands against him now,

no wall, no citadel left to break down–

except Saragossa, high on a mountain.

King Marsilion holds it, who does not love God,

who serves Mahumet and prays to Apollin.

He cannot save himself: his ruin will find him there. AOI.

-Translated by Frederick Goldin

Charles the great King, lord of the land of France,

Has fought beyond the hills for seven years,

And led his conquering host to the land’s end.

There is but one of all the towns of Spain

Unshattered–grim Saragossa, mountain-girt,

Held by Marsila, King of Spain, of those

Who love not God and serve false gods of stone

Brought from the shores of Araby.–Happless King!

Your hour is come, for all your gods of stone.

-Translated by Frederick Bliss Luquiens

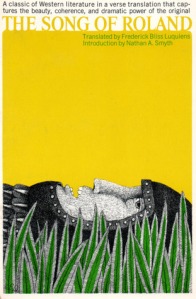

The Song of Roland

The Song of Roland, translated by Frederick Bliss Luquiens, 5/5

The Song of Roland, translated by Frederick Bliss Luquiens, 5/5

This epic tale of the betrayal and death of Roland at the hands of the Saracens clearly belongs in the company of other great epics, such as Gilgamesh, the Iliad and Beowulf. There is a timelessness and inevitability to the events in this poem that make you forget for a while that mythical heroes don’t walk the earth (though villains of mythical stature seem to). In my opinion, Luquiens’ translation in unrhymed iambic pentameter is tasteful and conveys poetic beauty without pretension.

Why I read it: one of those famous works I’d heard about but never actually read. Update: now I’ve read two versions–here’s a link to my review of the second.

Steal Like An Artist

Steal Like An Artist: 10 Things Nobody Told You About Being Creative by Austin Kleon, 5/5

Steal Like An Artist: 10 Things Nobody Told You About Being Creative by Austin Kleon, 5/5

The 10 points about creativity that form the backbone of this little book are deceptively simple (even unimpressive) at first glance. Happily, my first impression was wrong–the author uses this list merely as a starting point for an encouraging and inspiring discussion about artistic creativity. Reading this book first normalised, then challenged, many of the negative feelings that have caused me in the past to describe myself as an uncreative person.

- Steal like an artist.

It’s refreshing to hear someone creative admit that “every new idea is just a mashup or a remix of one or more previous ideas” (9). - Don’t wait until you know who you are to get started.

- Write the book you want to read.

This is so much more inspiring than the advice to “write what you know.” - Use your hands.

- Side projects and hobbies are important.

Having a wide variety of interests can be difficult and it’s sometimes tempting to feel like a loser for not focusing on just one. Kleon doesn’t make a particularly convincing case for his advice of “don’t throw any of yourself away” (68), but I do like the idea that “what unifies your work is the fact that you made it” (72). - The secret: Do good work and share it with people.

- Geography is no longer our master.

- Be nice. (The world is a small town.)

- Be boring. (It’s the only way to get work done.)

It may not be living the dream, but having a boring day job can give you the financial freedom to pursue creative endeavors. Kleon points out that, contrary to instinct, “establishing and keeping a routine can be even more important than having a lot of time” when it comes to being creative (124). - Creativity is subtraction.

Why I read it: Imgur user morganic mentioned this book in a comment on a photography post.

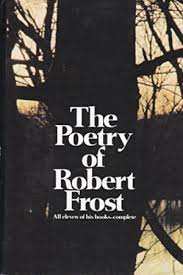

The Poetry of Robert Frost

The Poetry of Robert Frost: All eleven of his books–complete by Robert Frost, 5/5

The Poetry of Robert Frost: All eleven of his books–complete by Robert Frost, 5/5

I will always have a soft spot for Frost because his “Mending Wall” was the first poem to challenge my stubborn belief as a teenager that poetry must rhyme to be enjoyable. That poem helped me develop an appreciation for the wordsmithing that can be involved in the creation of blank verse and enabled me to enjoy much more of this collection than I would have so many years ago. Perhaps part of what makes Frost accessible is his evident love of nature, his ability to find inspiration in simple things and his avoidance of the self-indulgent, wilful obscurity that plagues so much art, in my opinion (i.e. if you can’t understand it, that must mean the creator was a genius, and if you can manage to read deep meaning into it, guess what…the creator must have been a genius).

Why I read it: I think I originally bought this to send to my brother because he doesn’t like poetry much…yet. Unfortunately for him, I think I must keep it instead.

Because I can’t resist, here are just a couple of my favourite poems from this collection (of which they are not strictly representative):

REVELATION

We make ourselves a place apart

Behind light words that tease and flout,

But oh, the agitated heart

Till someone really find us out.

‘Tis pity if the case require

(Or so we say) that in the end

We speak the literal to inspire

The understanding of a friend.

But so with all, from babes that play

At hide-and-seek to God afar,

So all who hide too well away

Must speak and tell us where they are.

BOND AND FREE

Love has earth to which she clings

With hills and circling arms about–

Wall within wall to shut fear out.

But Thought has need of no such things,

For Thought has a pair of dauntless wings.

On snow and sand and turf, I see

Where Love has left a printed trace

With straining in the world’s embrace.

And such is Love and glad to be.

But Thought has shaken his ankles free.

Thought cleaves the interstellar gloom

And sits in Sirius’ disc all night,

Till day makes him retrace his flight,

With smell of burning on every plume,

Back past the sun to an earthly room.

His gains in heaven are what they are.

Yet some say Love by being thrall

And simply staying possesses all

In several beauty that Thought fares far

To find fused in another star.

ESCAPIST–NEVER

He is no fugitive–escaped, escaping.

No one has seen him stumble looking back.

His fear is not behind him but beside him

On either hand to make his course perhaps

A crooked straightness yet no less a straightness.

He runs face forward. He is a pursuer.

He seeks a seeker who in his turn seeks

Another still, lost far into the distance.

Any who seek him seek in him the seeker.

His life is a pursuit of a pursuit forever.

It is the future that creates his present.

All is an interminable chain of longing.

There Was a Horse

There Was a Horse: Folktales from Many Lands, selected by Phyllis R. Fenner, 5/5

There Was a Horse: Folktales from Many Lands, selected by Phyllis R. Fenner, 5/5

This enjoyable collection of horse-themed legends from a variety of cultures is most notable for its fantastic pen and ink illustrations by Henry C. Pitz.

Why I read it: the title and spine detail caught my eye in a bookstore.

Mörder Guss Reims

Mörder Guss Reims: The Gustav Leberwurst Manuscript, translated and annotated by John Hulme, 5/5

Mörder Guss Reims: The Gustav Leberwurst Manuscript, translated and annotated by John Hulme, 5/5

Inspired by Mots d’Heures: Gousses, Rames, these German verses sound, when read aloud, like Mother Goose rhymes being spoken in accented English.

You can give it a try if you’re in private (or not easily embarrassed):

Little Bo-peep has lost her sheep,

And doesn’t know where to find them;

Leave them alone, and they will come home,

Bringing their tails behind them.

Liesel Bopp hieb es Schloss der schieb

An Dutzend Noor, wer zu Feind dem,

Lief dem Aal ohn’ an Tee willkomm Ohm;

Brenken der Teil Spee ein dem.

Compared to the French version of this concept, I found the rhymes much easier to recognize in German. I also liked that this edition had all the English verses in the back, so I didn’t have to resort to Google for translations nearly as often.

Why I read it: while researching Mots d’Heures, I learned about this book and bought a copy immediately. I sing in German a lot (in fact, this weekend I’m performing in Bach’s St. John Passion), so this is great practice and fun.

Mots D’Heaures: Gousses, Rames

Mots d’Heaures: Gousses, Rames: The d’Antin Manuscript edited and annotated by Luis d’Antin Van Rooten, 5/5

Mots d’Heaures: Gousses, Rames: The d’Antin Manuscript edited and annotated by Luis d’Antin Van Rooten, 5/5

This might be the strangest and most ingenious premise for a book I have ever seen–even after reading it, I still don’t really see how it’s possible. It is a collection of poems written in French that, when read aloud, sound like Mother Goose rhymes being read in English with a thick French accent. The author supplies entertaining footnotes that attempt, with varying degrees of success, to make sense of the “original” French.

Here’s an example for “Little Bo Peep”:

Little Bo Peep

has lost her sheep

and doesn’t know where to find them;

leave them alone and they will come home

wagging their tails behind them.

Lille beau pipe

Ocelot serre chypre

En douzaine aux verres tuf indemne

Livre de melons un dé huile qu’aux mômes

Eau à guigne d’air telle baie indemne.

Why I read it: My friend, Alison (whose own book, Entropy Academy, is soon to be released), gave this book to me while I was taking a French language class. Hearing the verses read aloud in her English accent was a hilariously bizarre experience.

N.B. There is a German version of this concept called Mörder Guss Reims.

Aku-Aku

Aku-Aku: The Secret of Easter Island by Thor Heyerdahl, 5/5

Aku-Aku: The Secret of Easter Island by Thor Heyerdahl, 5/5

This account of the first serious archaeological expedition to Easter Island could not be more exciting if it were set on a different planet entirely. Heyerdahl and his crew unearthed ancient statues, carvings and structures that had never been seen by outsiders before and some of their finds amazed the native residents as much as themselves. Even second-hand, the thrill of exploration and discovery was intoxicating. I did experience moral qualms caused by the author’s sometimes manipulative approach to wheedling secrets out of the islanders and it was a bit disturbing how willingly they seemed to trade their ancient artifacts for cigarettes. Still, it wasn’t a completely one-sided relationship–the expedition uncovered new statues, shed light on the island’s history, corroborated some of the local legends and encouraged the native people to remember their past and even revive some almost-forgotten traditional skills.

Why I read it: I’ve been an admirer of Heyerdahl since reading Kon-Tiki and wanted to read this book also before visiting the Kon-Tiki museum in Oslo, Norway, with my brother next month.

A picture quote I made:

Historians’ Fallacies

Historians’ Fallacies: Toward a Logic of Historical Thought by David Hackett Fischer, 5/5

Historians’ Fallacies: Toward a Logic of Historical Thought by David Hackett Fischer, 5/5

Fallacies everywhere! Browsing through eleven categories of faulty reasoning, all illustrated by examples from published works of historical scholarship, made me feel like a kid in a candy shop. My initial reservation–that it isn’t very respectable to do nothing but pick apart the works of one’s colleagues–was satisfactorily addressed in Fischer’s deliciously cogent introduction to the book. Here, the author acknowledges the dual impossibility and necessity of defining a logical approach to the study of history and justifies his negative method with the respectable goal “to extract from these mistakes [in other historians’ reasoning] a few rough rules of procedure” (xviii).

Though some may find his approach off-puttingly critical, the author is no intellectual slouch–many of the fallacies he addresses are so subtle that I am impressed he could identify them at all, much less find relevant examples in the wild. Though the topic is very specific, the application is broad–historians aren’t the only ones who are susceptible to fallacies of question-framing, factual verification, factual significance, generalization, narration, causation, motivation, composition, analogy, semantical distortion and substantive distraction.

Why I read it: The title caught my eye as I was browsing through Easton’s Books. The owner was so surprised that someone was actually interested in the book (he’d almost thrown it out, thinking no one would ever buy it) that he gave me a discount and said I’d made his day.

The Terrible and Wonderful Reasons Why I Run Long Distances

The Terrible and Wonderful Reasons Why I Run Long Distances by Matthew Inman (aka The Oatmeal), 5/5

The Terrible and Wonderful Reasons Why I Run Long Distances by Matthew Inman (aka The Oatmeal), 5/5

Inman’s reasons for running may be much more terrible and wonderful than my own (just as his conception of “long distances” is much longer), but a lot of this hilarious book resonated with me. On a side note: I’ve never read a collection of comics containing more illustrations of Nutella.

[Why I read it: I enjoy Inman’s webcomic, The Oatmeal, and this book came up in conversation with one of Dad’s coworkers. I’d actually almost bought it in a store just a few days previous before remembering that 5 Very Good Reasons to Punch a Dolphin in the Mouth was collecting dust on my shelf after being read just once. I hit the library up instead, which I guess makes me a bad fan.]