Tagged: 11th century

The Song of Roland

The Song of Roland, translated by Frederick Goldin, 5/5

The Song of Roland, translated by Frederick Goldin, 5/5

I can’t say I enjoyed reading this second translation of the epic poem as much as the first, but that is probably not a reflection of each version’s merit so much as the fact that reading The Song of Roland twice in two weeks is too much. Goldin’s translation is longer and seems much more true to the original from a grammatical point of view, but I found it to be less accessible than Luquiens’ version, which is more emotional and dramatic, while being less wordy. There is a sort of Old Testament rhythm and repetitive style to Goldin’s work that made it difficult not to zone out while reading.

Here is the opening laisse from each version for comparison:

Charles the King, our Emperor, the Great,

has been in Spain for seven full years,

has conquered the high land down to the sea.

There is no castle that stands against him now,

no wall, no citadel left to break down–

except Saragossa, high on a mountain.

King Marsilion holds it, who does not love God,

who serves Mahumet and prays to Apollin.

He cannot save himself: his ruin will find him there. AOI.

-Translated by Frederick Goldin

Charles the great King, lord of the land of France,

Has fought beyond the hills for seven years,

And led his conquering host to the land’s end.

There is but one of all the towns of Spain

Unshattered–grim Saragossa, mountain-girt,

Held by Marsila, King of Spain, of those

Who love not God and serve false gods of stone

Brought from the shores of Araby.–Happless King!

Your hour is come, for all your gods of stone.

-Translated by Frederick Bliss Luquiens

The Song of Roland

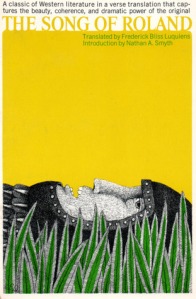

The Song of Roland, translated by Frederick Bliss Luquiens, 5/5

The Song of Roland, translated by Frederick Bliss Luquiens, 5/5

This epic tale of the betrayal and death of Roland at the hands of the Saracens clearly belongs in the company of other great epics, such as Gilgamesh, the Iliad and Beowulf. There is a timelessness and inevitability to the events in this poem that make you forget for a while that mythical heroes don’t walk the earth (though villains of mythical stature seem to). In my opinion, Luquiens’ translation in unrhymed iambic pentameter is tasteful and conveys poetic beauty without pretension.

Why I read it: one of those famous works I’d heard about but never actually read. Update: now I’ve read two versions–here’s a link to my review of the second.