Tagged: Nonfiction

Shakespeare’s Fingerprints

Shakespeare’s Fingerprints by Michael Brame & Galina Popova, 1/5

This is one of the most ludicrous books I have ever read and I could not stop talking about it to my poor husband, who also had to listen to a soundtrack of shocked snorts, giggles, gasps and groans as each page revealed some new absurdity.

The authors disagree with the scholarly consensus that William Shakespeare was a common actor from Stratford-upon-Avon, instead believing that his name was used as a pseudonym by Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford. The most convincing basis for this belief is a timeline of biographical events from de Vere’s life that seem to be referenced in Shakespeare’s plays and poems (assuming these works are semi-biographical, which the authors in no way prove).

Unfortunately, any reasonable and interesting points are obscured by inane literary analysis using criteria so broad that it soon loses all meaning. The authors start by claiming that Shakespeare’s use of certain common letters and combinations (e.g. o, vo, wo, vvo, eo, ver, fer, fair, etc.) should be interpreted as a purposeful play on the letters and sounds in de Vere’s name and title–a “fingerprint” clue to the author’s real identity. Not satisfied with co-opting such a large number of very common words to support their hypothesis, they then proceed to compare Shakespeare’s writing with other literary works of the time, identifying any similar metaphors, phrases, topics, rhyming word choices, poetic forms, even basic grammatical structure, as “proof” that de Vere was the real author. Ultimately, their tortured reasoning forces them to conclude that de Vere used no less than 37 pseudonyms (many representing real people who were alive at the time) and was single-handedly responsible for the development of 16th-century English literature.

Frustratingly, the authors focus on fluffing up ridiculous arguments with academic terminology in an effort to sound erudite, meanwhile studiously avoiding the performance of any real research that would prove or disprove their hypothesis. I really can’t emphasize enough how absolutely embarrassing and ridiculous the end result is. It’s difficult to write a review because the more detail I try to include, the more we fall down the rabbit hole of insanity. By keeping my analysis fairly short, I am not over-simplifying their arguments, but portraying them in a better light than they appear after closer examination. Still, I can’t resist giving two specific examples of what the amused reader will encounter. At one point the authors analyze the adjective “sweet” thus: “sweet ≡ sv veet ≡ seventeenth Vere” (99). Even the title Much Ado About Nothing is proof of Edward de Vere’s authorship in their eyes, since “Ad is most plausibly a play on Ed, the nickname of the genius lurking behind the Shakespeare pseudonym” (8). Insanity!

Oh, and if you are wondering, as I did, how not just one but TWO academics from the University of Washington could be behind this book, it might help clear things up to know that they were married at the time…

Why I read it: I bought it greatly discounted at a used bookstore many years ago.

What to Expect the Second Year

What to Expect the Second Year: From 12 to 24 Months by Heidi Murkoff and Sharon Mazel, 2/5

I found this book to be good primarily for two things: 1. confirming that all the craziness is normal and 2. making me thankful for all the craziness that we haven’t encountered. That said, I was disappointed by the same issues that bothered me in the previous book–namely, a laughably paranoid thoroughness that would be unhealthy in practice (if even attainable at all), and a patronizingly dismissive approach to non-mainstream points of view on controversial topics.

The sections on parenting and discipline were especially underwhelming, which was unfortunate because those are the topics about which I have the most burning questions. In effect, Murkoff associates all physical discipline with uncontrolled parental rage, providing as a substitute for this straw man a form of “discipline” that involves removing the source of temptation from the child or the child from the situation. This seems like a great strategy for handling delicate scenarios and other people’s children, but in my opinion, it is not discipline at all and fails to teach important lessons about self-control and boundaries that I know my almost-two-year-old is capable of learning.

Why I read it: It is very relevant to my life at the moment.

What If? 2

What If? 2: Additional Serious Scientific Answers to Absurd Hypothetical Questions by Randall Munroe, 5/5

He’s done it again! This sequel to What If? is laugh-out-loud funny and I enjoyed how the author used longer-running jokes throughout, as well as short-answer segments to add some [admittedly unneeded] variety.

Why I read it: I’m a fan of the author and his webcomic, xkcd.

Clanlands

Clanlands: Whisky, Warfare, and a Scottish Adventure Like No Other by Sam Heughan and Graham McTavish, 2/5

From a literary perspective, it’s frankly shocking that something so closely resembling a shared Google Doc rough draft somehow survived the publishing process and exists in book form. Unpolished, unfocused, and overflowing with “cringe,” this book waffles between authors’ perspectives just like it waffles between travelogue, memoir, history and reality TV pitch. There were a few humorous moments and interesting historical facts, but I don’t think it has much to offer anyone outside of its target audience–Heughligans and fans of Outlander. Perhaps surprisingly, given my opinion of the book, I did enjoy its associated TV show, Men in Kilts.

Why I read it: my mother-in-law generously lent me her brand new copy while we were on a hunting trip.

The Complete Morgan Horse

The Complete Morgan Horse by Jeanne Mellin, with illustrations by the author, 3/5

This 1986 compilation of two earlier books definitely shows its age but still retains some value as a collection of vintage Morgan photos, excellent artwork by the author, and a fairly detailed history of the breed. Mellin is a better artist than writer, and her prose tends to be a bit dry and repetitive, with a slightly patronizing tone. However, I was still fascinated to learn about the roots of this uniquely American horse breed and its influence on the American Saddlebred and the Standardbred.

Why I read it: I remember coveting this book when I checked it out of the library as a kid, and it finally dawned on me that I’m a grown-up now and can just buy a copy if I want.

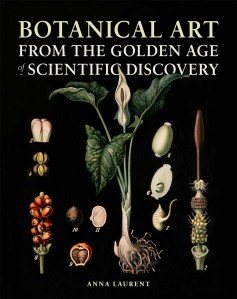

Botanical Art from the Golden Age of Scientific Discovery

Botanical Art from the Golden Age of Scientific Discovery by Anna Laurent, 5/5

I borrowed this book from the library just to flip through the pictures, but it turned out to be an unexpectedly delightful read. The text perfectly balances with the images, providing just enough additional information to capture the reader’s interest and encourage a more in-depth examination of the many botanical wall-charts it features.

Why I read it: a brief intention to create my own botanical art lead me to order all related books from the library (there weren’t many).

What to Expect the First Year

What to Expect the First Year by Heidi Murkoff, 3/5

My husband and I were fortunate enough to have the world’s most chill baby, so I didn’t bother reading most of this book until we were halfway through year two of parenthood. Though raising our little guy has definitely become more challenging as he matures, the first twelve months were relatively straightforward; most issues that came up were easily addressed by a quick internet search, knowledgeable friends and family, or at medical check-ups. I didn’t feel the anxious anticipation, curiosity, and solitariness of first-time pregnancy that made What to Expect When You’re Expecting so comforting and helpful. For me, this book occupies a weirdly unhelpful middle ground, at times too hyper-focused to be practical or too general to be a reliable source for researching complex issues (especially controversial ones like vaccinations or discipline).

Why I read it: a friend and parent of two young children recommended it very highly.

Scars and Stripes

Scars and Stripes: An Unapologetically American Story of Fighting the Taliban, UFC Warriors, and Myself by Tim Kennedy and Nick Palmisciano, 4/5

At some point (I don’t even remember when), I got it in my head that Tim Kennedy was kind of an obnoxious d-bag, so I had zero interest in reading what I was sure would be an obnoxious and terribly-written autobiography. I wouldn’t have even known it existed if my husband hadn’t listened to the audio book and then proceeded to tell me stories from it until I ordered it from the library just to get him to shut up.

I couldn’t put it down. In about one chapter, I went from “eh, it’s ok for what it is” to staying up late into the night trying to find a slightly boring spot to stop reading. It’s not great literature, but man, is it great stories!

Why I read it: a recommendation from my husband.

Solve for Happy

Solve for Happy: Engineer Your Path to Joy by Mo Gawdat, 4/5

If I wasn’t absolutely, abjectly ready to hear someone else say what my husband has been telling me for years, then I probably would have hated this book for its many cliches, general cheesiness, and cringy clip art. Though a highly intelligent and successful businessman, Gawdat is rather a layman in terms of psychology and philosophy, so one might expect that his contribution to the well-worn topic of “happiness” would be in a uniquely analytical approach to existing research, rather than any foundational insights. I was very surprised to find that this was not the case. In fact, the much-advertised “happiness equation” and concept of “solving for happy” seemed under-developed and forgettable to me. What will stick with me for a long time and, in fact, motivated me to copy all those “cheesy cliches” into a Word document for later reference, was three concepts: 1. the natural, default human state is happiness, 2. unhappiness is generally rooted in thoughts about the past or the future, and 3. mental suffering is useless.

These ideas fly in the face of what have been, up until now, my beliefs that 1. happiness is an otherwise unattainable by-product of pursuing a passion in life, 2. controlling every aspect of my life will compensate for my uncontrollable thoughts (and their accompanying emotions), and 3. suffering is necessary to stimulate personal growth. Frankly, these beliefs have not worked out that well for me over the last three decades and recently having a child has intensified my desire to enjoy every moment and make peace with my own existence, instead of obsessing over what the “point” of it all is.

Though it did not come from any of the many decorated philosophers or psychologists whose work I have read, and it can feel over-simplified and unreasonably optimistic at times, Gawdat’s perspective brought me immediate relief and seems to be in line with the life experience I have accumulated. I don’t expect everything to be sunshine and roses from now on, but (or maybe, and) I’m excited to apply this new perspective to each moment as best I can.

Why I read it: my dad sent me a link to an interview with Mo Gawdat, but I don’t have the attention span to watch slow, unstructured conversations, so I opted to read his book instead.

Think and Grow Rich

Think and Grow Rich by Napoleon Hill, 2/5

Just from the title and short author bio on the cover flap, I expected this book to be pure baloney, but I never expected to encounter such a bizarre combination of sound psychological principles, medieval science, “New Thought” spirituality, and grandiose (though entirely unsubstantiated) personal anecdotes.

First, the bad: Napoleon Hill was undoubtedly a committed conman and lifelong liar. Even if you don’t believe all of the unsavory claims in Matt Novak’s extensive exposé of Hill’s life (warning: it’s an almost 20,000-word monster of an article that will suck you in from beginning to end), you would have to be very credulous indeed not to spot numerous red flags that indicate the questionable character, yet unquestionable audacity, of Napoleon Hill. His main claim to credibility hinges on close personal association with an impudent list of famous, well-respected figures such as Andrew Carnegie, Thomas Edison, and multiple U.S. presidents. Unfortunately, all detailed records of these relationships were allegedly destroyed in a fire (eye roll) and Hill was wise enough to save his stories until the people in question were dead and thus unable to contradict his incredible claims. Even the tale he tells in Think and Grow Rich of his own son, born without ears but allegedly made to hear by the single-minded positivity that is a central tenet of the book, is at complete odds with a later article in which he credits chiropractics alone as the miraculous cure.

Despite the author’s personal shortcomings, this book is strangely motivating and encourages many proven strategies for success, such as goal-setting, visualization, positive thinking, forming good habits, and collaboration. If you can get past the mysticism and pseudoscience, there are some good things to be gleaned. For example, while I don’t agree with the extent to which Hill credits misfortune to negative thinking, I did feel challenged to reconsider the effect that negative thoughts might have on my life. For some reason, I can easily see the benefit of positive thinking, but view negativity as somehow neutral, which is clearly not the case.

Why I read it: Brazilian jiu-jitsu legend Rafael Lovato Jr. mentioned it in an interview.