Tagged: 4/5

Ghost Stories of Canada

Ghost Stories of Canada by Val Clery, 4/5

Ghost Stories of Canada by Val Clery, 4/5

This collection of short stories does not get off to a great start, opening with a stale tale that features a cliched haunted doll. Luckily, the rest of the book has a fun, Canadian flavour and shows off the author’s respectable story-telling skills and personal enthusiasm for the topic.

Why I read it: a thrift store find.

Spiritual Midwifery

Spiritual Midwifery by Ina May Gaskin, 4/5

Spiritual Midwifery by Ina May Gaskin, 4/5

Almost half of this book consists of childbirth stories told by members of The Farm, a counterculture community that peaked in the 1970s. It is both entertaining and educational to read about other people’s experiences, but there are a couple factors that affect the helpfulness of these personal accounts, in my opinion. Firstly, it is clear that most of the narrators are deeply invested in the particular form of spirituality and beliefs associated with The Farm. The way in which the shared experience of such a close community can affect an individual’s way of thinking and communicating is something an outsider must account for. For example, the words “psychedelic,” “trip,” and “aura” clearly have a deep and nuanced meaning to these people, but it’s a little unsettling to encounter such vocabulary in a book that also gives serious medical advice. All in all, while there was a lot of interesting and helpful info in this book, I found Gaskin’s Guide to Childbirth to be less dated, more accessible and more trustworthy in tone.

Why I read it: a friend recommended it to me.

The Time of Contempt

The Time of Contempt by Andrzej Sapkowski, translated by David French, 4/5

The Time of Contempt by Andrzej Sapkowski, translated by David French, 4/5

In this installment of the Witcher Saga, Sapkowski really dives into the politics of his fantasy world, a focus that I did not find particularly interesting though I appreciated the worldbuilding. In addition, a satisfying amount of interesting characters (some new, some old), exciting scenarios, and a somewhat elevated tone, raised this book in my opinion closer to the level of the first in the series.

Why I read it: I’m gradually working my way through the series.

Natural Childbirth the Bradley Way

Natural Childbirth the Bradley Way by Susan McCutcheon-Rosegg, with Peter Rosegg, 4/5

Natural Childbirth the Bradley Way by Susan McCutcheon-Rosegg, with Peter Rosegg, 4/5

I read this book for a laugh, expecting that almost 40 years of advancements in the field of medicine would have rendered it largely useless by now. To my surprise, I found myself being won over by the commonsense advice it presents, emphasizing mindful relaxation, supportive coaching, patience and faith in the natural process. After all, the act of childbirth is as old as time and if, as so many experts assert, we still experience primitive influences on a biological level, why should we rush to intervene with little excuse?

The Tale of Despereaux

The Tale of Despereaux: being the story of a mouse, a princess, some soup, and a spool of thread by Kate DiCamillo, 4/5

The Tale of Despereaux: being the story of a mouse, a princess, some soup, and a spool of thread by Kate DiCamillo, 4/5

This charming story begs to be read aloud near a cozy fireplace and I think even children too young to read would love hearing it. I appreciate that, in the style of all classic fairy tales, it does not shy away from portraying darkness to balance out the light. By acknowledging the violence and tragedy of existence in a matter-of-fact and age-appropriate way, the author puts a backbone in what might otherwise have been a silly, sappy, story for kids.

Why I read it: a student’s mom, Paige, recommended it in conversation.

Unsolved Mysteries of the Arctic

Unsolved Mysteries of the Arctic by Vilhjalmur Stefansson, 4/5

Unsolved Mysteries of the Arctic by Vilhjalmur Stefansson, 4/5

Written by a bona fide Arctic explorer, this book reflects a bygone era of exploration, when sane men packed up and left on insane adventures into unexplored territory from which they well knew they might never return. Indeed, every one of the five stories in this book involves death or disappearance, often punctuated by the horrors of starvation, betrayal, cannibalism and pure ineptitude. The author is not shy in drawing his own conclusions for each scenario and though his writing style is not the most entertaining, his first-hand experience and rational approach to the information available at the time make for a fascinating read.

I learned a lot from this book, such as that the Arctic, which I once imagined to be an abandoned ice desert, is (or at least, was) actually livable land, teeming with life. Unintuitively, the Inuit would move north during winter due to the abundance of game in the frozen landscape, killing everything from seals to polar bears without the aid of guns (often in territory in which well-armed Europeans managed to starve to death). I also learned a lot about scurvy, its causes and surprising psychological effects. According to Stefansson, scurvy plagued those explorers who tried to maintain a European diet, even when supplemented by fruits and vegetables. It was the author’s strong opinion that a diet consisting solely of native, fatty meat was the best way to stay healthy in the Arctic. It’s strange to think that the ketogenic diet is still controversial after over 80 years of arguments and studies.

Why I read it: an impulse buy in a used book store; for $3, who could resist?

House of Leaves

House of Leaves: A Novel by Mark Z. Danielewski, 4/5

House of Leaves: A Novel by Mark Z. Danielewski, 4/5

This book is so bizarre that I’m tempted to refer to it as this “book,” as if quotation marks will somehow convey its reality- and genre-bending strangeness. Its core is an incredibly inventive transcription of a fictional documentary film, wrapped in layers of contrived academic interpretations which are communicated via endless footnotes and interspersed with the stream-of-consciousness ramblings of an unreliable narrator, all while periodically diverting to tedious appendices. This mental obstacle course of a book ranges in tone from academic analysis to B-horror and it’s not much of an exaggeration to say it manages to check off nearly every know narrative technique.

The more I tried to analyze and understand House of Leaves, the more useless it felt, as if a “point” did not exist outside of attempts to explain it. By confounding literary (and non-literary) genres and techniques, the author creates his own layered reality, a house in which a reader can easily become lost and confused while trying to determine what actually exists both inside and outside of the leaves (pages) of the book. The whole experience stimulated me to re-consider how my perceptions and expectations shape my sense of reality, and to acknowledge the extent to which interpretation can create meaning instead of just conveying it. All-in-all, reading this book was a uniquely frustrating and rewarding experience.

Why I read it: my sister, Anna, was recommended it by a friend and passed it along to me with a somewhat ambivalent review.

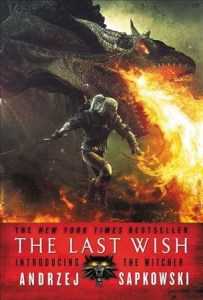

The Last Wish

The Last Wish by Andrzej Sapkowski,  translated by Danusia Stok, 4/5

translated by Danusia Stok, 4/5

I’m a bit of a fantasy snob to say the least, so it was a pleasant surprise to find that Sapkowski is a competent writer, capable of reworking the tired tropes of a well-worn genre instead of merely ripping them off. At times, he purposefully incorporates elements of popular fairy tales and legends into his own in a skillful way, making it almost seem as if his stories predate the originals. I found the book’s layout to be bewildering, but after learning from its Wikipedia article about the concept of a “frame story” interspersed with other short stories, it made a lot more sense. I am looking forward to reading more books in this series as soon as the library, currently closed thanks to the COVID-19 virus, re-opens.

Why I read it: I figured that any book series spawning popular video games and a Netflix show must be worth checking out.

Tribe

Tribe: On Homecoming and Belonging by Sebastian Junger, 4/5

Tribe: On Homecoming and Belonging by Sebastian Junger, 4/5

Disjointed, unscholarly, easily debatable and offering no real solutions, this book nevertheless makes a tiny but very specific contribution towards understanding the complexities of U.S. mental health issues. Junger postulates that mental health declines as societies lose their tribal features, becoming more complex, prosperous, elitist and individualistic. Further, he attempts to prove that people’s resilience actually increases in troubled times, when society temporarily becomes more communal and egalitarian. His final claim is that long-term PTSD in soldiers is not so much caused by wartime trauma, but the difficulty of transitioning between these two cultures.

Junger makes some controversial statements and is up-front about his book’s origin (a Vanity Fair article) and purpose (nonacademic). Because of this, I feel Tribe transcends its pop-psychology characteristics and can be forgiven for feeling like a very preliminary exploration of a complex topic.

Why I read it: When the title was recommended separately to me by two of my brothers, I knew it was worth checking out.

When God Laughs

When God Laughs by Jack London, 4/5

When God Laughs by Jack London, 4/5

The short story has never been one of my favorite literary forms, so I was not exactly jazzed to crack open what I thought was a Jack London novel to find a collection of twelve shorter works under one title. They say a brief speech requires much more effort to create than a long one and I can only assume that even the best novelists face a similar challenge when it comes to crafting shorter works. My mild pessimism was wasted in this case, however, because most of these stories were captivating–full of vivid characters and a variety of dramatic plots and settings. It is a testament to the author’s skill that I could become so emotionally invested in stories ranging from just ten to forty-two pages long.

Why I read it: Just trying to read through the old books on my shelf!